Anna Sedláčková holds a specialised Bachelor’s degree in Eastern European Studies from Charles University in Prague and is among the last cohort of students to graduate with a Master’s degree in Baltic Studies. ‘The Baltic Studies programme at this university has been discontinued. Students can still learn Lithuanian and Latvian as a second language, but now there is no separate dedicated programme,’ remarked Anna.

‘Every language is worth learning, but Lithuanian stands out as a unique linguistic gem. Lithuania has always been a remarkable example of how to preserve and cherish language and culture. We Czechs seem to have forgotten these things. So, if we want to learn something about ourselves, we should start following such great examples,’ she said.

‘First, I fell in love with the country, and then with its language’

After graduating from high school, Anna spent a month in Latvia and Lithuania: ‘First, I fell in love with the country, and then with its language. Having returned to Czechia, I started reading Lithuanian and Latvian literature translated into Czech. I soon realised I wanted to delve into these books in their original languages, which led me to study Latvian at university and, later, Lithuanian.

During her Bachelor studies, Anna was also learning Chinese, but the COVID-19 pandemic altered her life plans. As she could not pursue her opportunities in China, Anna redirected her focus to Baltic studies.

‘I love the fact that studying the Baltic languages allows us to observe how they have remained almost unchanged over time. The history of both Latvia and Lithuania is complicated, but they have managed to preserve the greatest treasures – their languages,’ noted Anna.

Anna translates literature from Latvian and Lithuanian into the Czech language: ‘Together with my colleague Inese Pintane, I translated Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s book ‘Lietuviai prie Laptevų jūros’ (‘Lithuanians by the Laptev Sea’). I hope it will be published next year. It is important that not only Lithuanians but also the rest of the world knows what happened in Lithuania and what Lithuanians were forced to endure.’

Other works translated by Anna and published this year in the Czech Republic are ‘Mano tėtis rašo knygą’ (‘My Dad is Writing a Book’) by Tomas Dirgėla and ‘Akmenėlis’ (‘The Pebble’) by Marius Marcinkevičius. The children’s book ‘Laimė yra lapė’ (‘The Fox on the Swing’) by Evelina Daciūtė will be a new release next year. Anna is passionate about bringing Lithuanian literature to Czech readers. This year also saw the publication of an anthology of contemporary Latvian literature, edited and translated by Anna. Similar anthologies of Estonian and Lithuanian literature that Anna is already working on are expected to be published in the next two years.

However, according to the linguist, we still lack translations from Lithuanian into Czech. ‘In Czechia, there was a very strong tradition of translating Lithuanian works. Between World War I and 1989, over 60 Lithuanian books were translated. However, the interest waned after 1989. We translators would like to change this. For instance, Věra Kociánová, translator and director of the publishing house ‘Venkovské dílo’, translates books from Lithuanian into Czech and publishes them, e.g. ‘Tūla’ by Jurgis Kunčinas, children’s books by Kęstutis Kasparavičius, and some poems by Tomas Venclova. Most publishing houses are usually hesitant to translate books from Lithuanian, favouring major languages such as French or German. But we have managed to prove that Lithuanian and Latvian literature is equally valuable, so hopefully, there will be more and more translations published,’ she said.

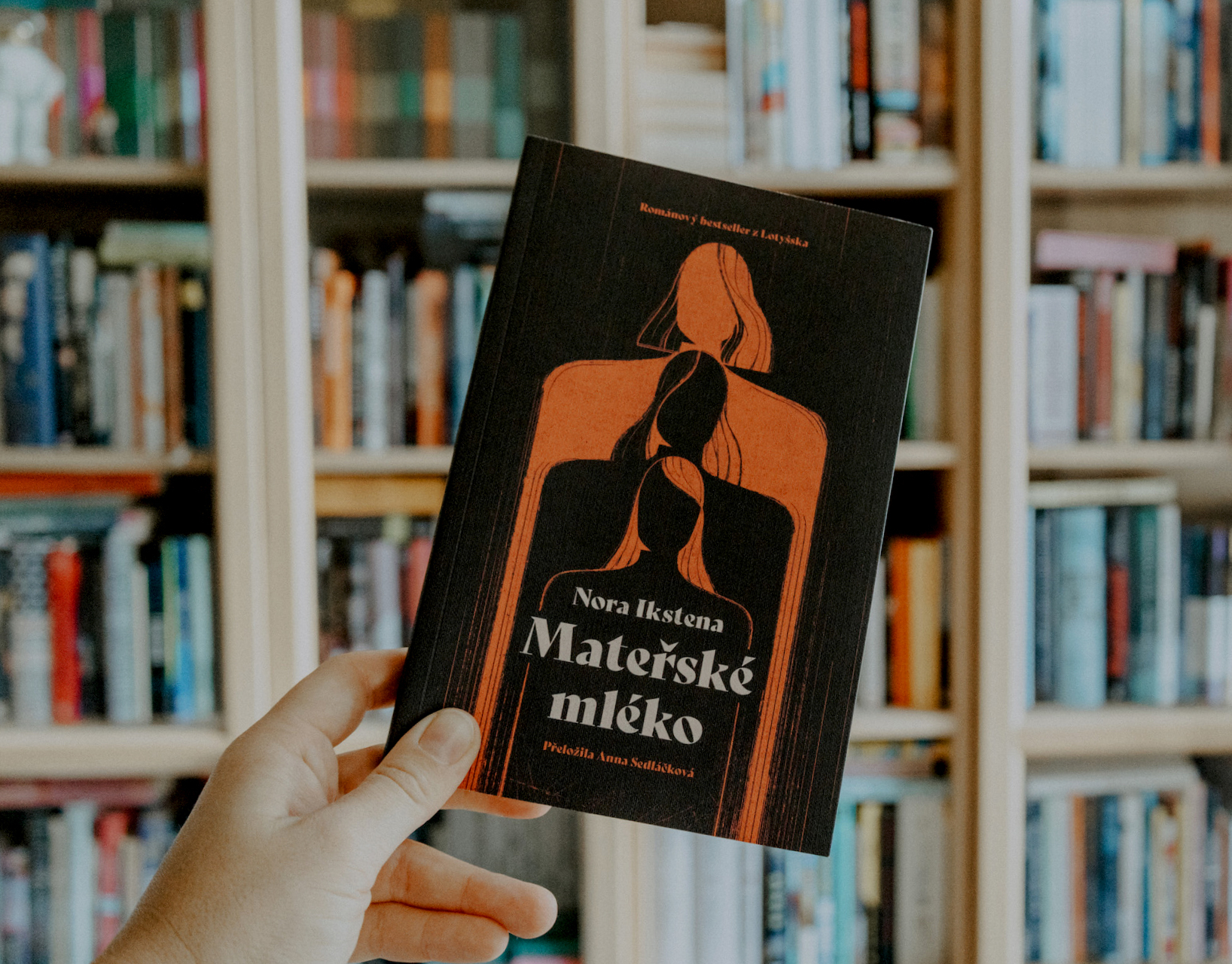

Anna Sedláčková is delighted to see translations from the Baltic languages gaining growing recognition in the Czech Republic. ‘I translated Nora Ikstena’s book ‘Mātes piens’ (‘Soviet Milk’). In my country, this was the first translation from the Latvian language in 15 years. It received multiple nominations, proving that Baltic literature can attract both readers and publishers.’ Anna plans to continue translating Lithuanian and Latvian books.

Exploring the vitality of the Baltic languages

Currently pursuing her Master’s degree at the University of Helsinki, Anna is researching the vitality of the Baltic languages. ‘I’m comparing the Karaim language in Lithuania, the Livonian language in Latvia, and the Võro language in Estonia. I want to know how official policies toward minority languages differ in the Baltic States and examine how people feel about these languages: what challenges do Karaim, Livonian, and Võro speakers face? What changes do they believe are necessary for the country’s language policy, such as the status of the language or attitudes towards it? Do they need more language courses, additional resources, or books in these languages? What do they feel is missing to help them improve their proficiency in these languages? Are Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia doing enough to protect these languages, or could they do more? I learnt a lot from the interviews and I believe that the relevance of my research stretches beyond the Baltic context,’ asserted Anna, who intends to continue to develop this topic during her doctoral studies.

Anna Sedláčková has also taught Lithuanian and Czech in Helsinki: ‘These courses were aimed at Finns and other Finnish speakers. In Helsinki, there are plenty of opportunities to study languages and other subjects during your free time. In my opinion, my students performed very well. Although I was a bit worried about their ability to pronounce consonants like č, š, and ž, as well as grasp Lithuanian grammar, they exceeded my expectations.’

She is happy with her students, as they are all eager to continue their Lithuanian studies. Currently, Anna works as a researcher at the Livonian Institute, where she applies her knowledge of the Livonian language and collaborates with a team of experts on documenting and promoting this Finno-Ugric language.

The Department of Baltic Studies at the VU Faculty of Philology continues its series of articles featuring alumni from foreign centres of Baltic studies. After graduation, they not only continue to deepen their knowledge of Lithuanian but also integrate the Lithuanian language, literature, and culture into their professional activities.

This article is part of the project ‘Information and Coordination Portal of Baltic Studies Centres’ (No. 1.78 Mr SU-1006) implemented by the Department of Baltic Studies at the VU Institute for the Languages and Cultures of the Baltic and supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport of the Republic of Lithuania.

Prepared by Dr Veslava Sidaravičienė, Research Assistant at the Department of Baltic Studies of the Institute for the Languages and Cultures of the Baltic of Vilnius University